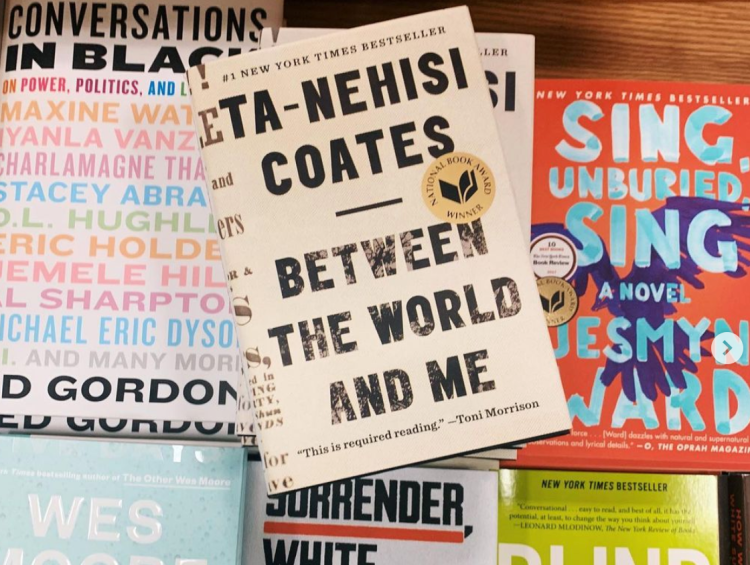

Publisher: Spiegel & Grau Page Count: 152 Year Published: 2015 *Anti-Racist Reading List*

Synopsis: In a profound work that pivots from the biggest questions about American history and ideals to the most intimate concerns of a father for his son, Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a powerful new framework for understanding our nation’s history and current crisis. Americans have built an empire on the idea of “race,” a falsehood that damages us all but falls most heavily on the bodies of black women and men—bodies exploited through slavery and segregation, and, today, threatened, locked up, and murdered out of all proportion. What is it like to inhabit a black body and find a way to live within it? And how can we all honestly reckon with this fraught history and free ourselves from its burden?

Between the World and Me is Ta-Nehisi Coates’s attempt to answer these questions in a letter to his adolescent son. Coates shares with his son—and readers—the story of his awakening to the truth about his place in the world through a series of revelatory experiences, from Howard University to Civil War battlefields, from the South Side of Chicago to Paris, from his childhood home to the living rooms of mothers whose children’s lives were taken as American plunder. Beautifully woven from personal narrative, reimagined history, and fresh, emotionally charged reportage, Between the World and Me clearly illuminates the past, bracingly confronts our present, and offers a transcendent vision for a way forward.

TW: police brutality, racism, slavery

This book is important. I listened to this, but I plan to revisit it in hard copy in the future. While brief, it holds so much weight. Add to your TBR, friends.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes a letter to his son, chronicling his own awakenings to his place in the world and the complexities of living in his body and country and world with an urgency that cautions but encourages. In his letter, Coates grapples with questions of self-discovery, racism, the idea of race, and dissects why it is deeply important to engage critically with history. Coates writes, “Black people love their children with a kind of obsession. You are all we have, and you come to us endangered.” This made me think about the history that helped mold this sentence. Specifically, it made me think about a conversation with my uncle and I had when I was younger. My uncle is Black and we were talking about his familial history and his enslaved ancestors. He was sharing his thoughts about slavery and its long-term repercussions, and how families were purposely broken down and sold as parts to ensure further dehumanization of the enslaved. From the beginning, Black parents had a higher likelihood of losing their children. When we consider the deaths of Philando Castille, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor we see children that parents must grieve or parents that children must grieve. There is an argument that to question American history is to be un-American or to hate the country. I disagree. There is a moral responsibility to engage with history, to question it, and to prevent the repetition of past transgressions. Further, if we fail to learn and understand history as it happened and not as we’re told, we cannot possibly trace the injustices that persist today. It’s as if the threads that wind through history become invisible strings, blinding us to the fact that we have injustices today, and further, why we have the injustices we do today. To ignore the intentional breakdown of black families during slavery is to discredit the deaths of black Americans who die at the hands of an institution (e.g., the police).

In his letter, Coates writes, “My work is to give you what I know of my own particular path while allowing you to walk your own.” Coates tries to caution his son against the realities of being black in America while also encouraging his son to forge his own path, one that is cognizant of history and wary of the present. I was particularly interested in Coates’s thoughts about intentions. I was thinking primarily about contextualized intentions and what they mean when measured against real impacts. I say “contextualized” because intentions are formed from a certain context. Context that, depending on how it is relayed, can mean very different things and can, at times, be used to erase impact. To explain intentions with context may mean “I didn’t mean to and I recognize the impact but here are three thoughts I had when I did the thing.” The person impacted may view the context as excuses while the person offering the context may consider the points as justifications or mitigating factors. Or rather, justifications meant to make behavior excusable. Coates writes, “The point of this language of ‘intention’ and ‘personal responsibility’ is broad exoneration. Mistakes were made. Bodies were broken. People were enslaved. We meant well. We tried our best. ‘Good intention’ is a hall pass through history, a sleeping pill that ensures the Dream.” This got me thinking about so many facets of life and how language we use to right our wrongs results in erasure of the problem by simply applying apologies to the wound rather than understanding the injury.

My thoughts are a bit rambly, but this book carries thought-provoking points on every page. 💛